ABSTRACT

Polygonum plebeium R. Br. (Family: Polygonaceae) is commonly known as “small knotweed”. It is used as a traditional medicine by many cultures across the world. In the rural communities of Shahjahanpur, Uttar Pradesh, it has long been practised to treat intestinal symptoms and pneumonia orally, while leaf powder combined with mishri is offered to treat menstruation disorders. It is abundantly found in the regions of Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. It consists of numerous phytochemicals, such as alkaloids, essential oils, flavonoids, phenols, and tannins , and possesses a variety of pharmacological activities, including anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antinociceptive, cytoprotective, and neuroprotective effects. P. plebeium extract has a wide range of pharmacological properties and is used in the treatment of diarrhoea, eczema, inflammation, liver illness, and ringworm. In this review, a comprehensive and methodical search was performed in several prominent scientific databases, such as the Google Scholar, PubMed, Research Gate, Scopus, Science Direct, and Web of Science.

INTRODUCTION

It is believed that more than 80% of the world’s population prefers the use of herbal treatments for the treatment of basic ailments.1 Over 60% of the globe’s population uses traditional medicinal plants to treat various health conditions.2 In poor countries, 80% of the population uses traditional medicinal plants for treatment of various illnesses. Herbal medicine enjoys widespread popularity globally, with particular prominence in South Asian countries such as India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.3 The use of herbal remedies has been widely advocated for the therapeutic management of several medical conditions. Plant resources are widely recognized as valuable natural materials for the advancement of innovative pharmaceuticals on a global scale. Herbal treatments are becoming more popular because people believe plants, being close to nature, are safer than synthetic drugs. Plants have several benefits over modern medicine, including their low cost, their ease of availability, and the fact that they cause less adverse reactions.4 The importance of doing research in the field of medicinal plants lies in its potential to uncover new medicinal compounds derived from indigenous plant species that hold worldwide significance.5 A diverse range of medicinal species are employed for their therapeutic properties in alleviating human ailments, as well as for applications in cosmetics, flavourings, essential oils, bittering agents, spices, sweetening agents, insect repellents, and colouring agents.6

Polygonum plebeium R.Br. (family: Polygonaceae), is commonly referred to as “small knotweed” in the English. The genus Polygonum consists of approximately 250 plant species, including both annual and perennial varieties. The plants have a broad distribution, ranging from northern temperate to tropical and subtropical regions. The plant flourishes in wet conditions, specifically in areas with low elevation near streams and rivers. P. plebeium is commonly observed in close proximity of rivers, canals, dried-up lakes, and cultivated rice fields. The growth of the plant is determined by the composition of clayey soil and the fluctuating levels of water logging it experiences annually.7

Pharmacognosy

Taxonomical classification

- Root-Root

- Kingdom-Plantae

- Phylum-Tracheophyta

- Class-Magnoliopsida

- Order-Polygonales

- Family-Polygonaceae

- Genus-Polygonum

- Species-Polygonum plebeium

Vernacular name

P. plebeium has many different names that vary depending on the languages spoken in a specific geographical area. Here are the plant vernacular names used across Indian subcontinent (Table 1).

| Country of origin | Vernacular names |

|---|---|

| India | Bengali: Chemti Sag, Khudi Bisakamtali, Mechuya Shaak, Raniphul; English: Small Knotweed; Gujarati: Zinako Okhrad; Hindi: Chimati Saag, Lal Buti, Machechi; Kachchhi: Ratanjot; Kannada: Kempu Nela Akki, Siranige Soppu; Malayalam: Peraraththa; Manipuri: Tarakman; Marathi: Gulabi Godhadi; Mizo: Bakhate; Nepali: Balune Saag, Bethe, Latte Jhaar, Masino Pire, Sukul Jhaar; Odia: Muthisag; Sanskrit: Sarpakshee, Sarpalochana; Telugu: Chimati Kura. |

| Bangladesh | Chemti sag, Dubia Sag, Anjaban. |

| Pakistan | Hind raani. |

Botanical description

P. plebeium is a perennial herb, highly branched, that can reach a length of up to 30 cm. The stems and branches of woody plants are originating from a central base. The leaves are oblong, with a size range of 0.5-10 mm in length and 1.2-3.2 mm in width, and have smooth edges with lack of hairs. The nerves on the leaves are not prominent, and the petiole is sessile. The stipules are ciliate and have a whitish colour. Ochrea, which is a tubular sheath formed by the fusion of two stipules around a stem, measures 1-2 mm in length. It is membranous and has an ovate shape. The flowers are small, measuring approximately 0.2 mm in diameter. They are typically white, sometimes with a pinkish hue, and are found singly in the axils of the plant. They have flower-stalks that are 1.5 mm long during flowering and are typically surrounded by Ochrea. They measure approximately 1-2 mm in diameter and have very short stalks. The tepals of the plant have a total of five parts, with three outer tepals and two inner tepals. They are inverted-lance shaped, with unequal sizes. The outer tepals are slightly longer and pointed, while the inner tepals are blunter. The anther is ovoid, 2-celled, 0.2 mm long, and reddish in colour. The ovary is 3-gonous, measuring 0.5 mm in length and having a greenish colour. It is 1-loculed and contains only one ovule. The style is 3-fid, thick, and measures 0.2 mm in length. The stigma is terminal and subcapitate, appearing pinkish in colour. The net lets are sharply trigonous, measuring 0.1 mm in diameter, and possess a persistent style. They have a shiny and glabrous appearance. The stamens consist of five filaments that are long and have a broadened base, and they are all of equal length. The ovary is small and has a trigonous shape, characterized by three styles and capitate stigmas. The nuts are small, ranging from 1.0 to 1.75 mm in length. They have a circular to ovate shape and appear shiny, black, and devoid of hair. The period of flowering and fruiting occurs from October to March.8

Cultivation and Propagation

P. plebeium is favourably grown in conditions ranging from full sun to partial shade. The soil conditions in which this species grows are best when they are moist and cultivated, but they can tolerate some drought. This plant species also flourishes well-drained; with a maximum altitude range of 1250 m. Propagation commonly occurs through seed or root system division.

Distribution

P. plebeium is widely distributed across several regions of world, including Australia, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, North America and Sri Lanka. The species is indigenous to Madagascar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and many regions in India, including Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Daman, Goa, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal. It is distributed in India across a wide altitudinal range, spanning from sea level to approximately 2200 m in the Himalayan region.7

Traditional uses

P. plebeium is reportedly used as a famine food in the tribal communities of Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Orissa. It locally known as a Muthisag in the state of Orissa, and is utilized for the treatment of pneumonia.9 It has been utilized in the treatment of menstruation disorders with the administration of its leaf powder in combination with mishri.10 P. plebeium powder is orally administered for the treatment of pneumonia and gastrointestinal disorders. The practice of using powdered substances has been observed among the native people of the Lakhimpur region in Assam.11 In addition to their therapeutic applications for urinary infections and digestive disorders, crushed leaves have been employed for the removal of dandruff from hair and as an ingredient in perfume formulations.12,13 The rural population of Sivagangai, Tamil Nadu, India, has employed a paste obtained from the roots of P. plebeium that is applied twice daily to relieve inflammation.14 The aqueous plant extracts from P. plebeium, also known locally as “Hind Raani” in the Kotli district of Pakistani, have long been used as a tonic to treat pneumonia and intestinal disorders. The whole plant extract is traditionally used for its analgesic, anthelmintic, astringent, and purgative. The plant’s aqueous extract is used as a tonic in the treatment of respiratory infections like pneumonia and digestive problems like diarrhoea. The whole plant juice is preferred because it has expectorant, diuretic, and vasoconstrictive properties.15,16 In Pakistan, people residing in rural areas have traditionally utilized certain remedies for addressing a range of health concerns, such as liver illness, inflammation, dysentery, eczema, and ringworm.17 The communities residing near the Chenab River in Punjab province, Pakistan, have utilized 129 medicinal plants, including P. plebeium, for the treatment of various ailments. The traditional use of P. plebeium includes oral administration of decoction prepared from its root and shoot, as well as consumption of leaf extract and whole plant powder. These remedies are believed to be effective in treating conditions such as galactagogue, pneumonia, liver tonic, heartburn, and promoting regular bowel movements. Additionally, the external use of P. plebeium paste is used in the treatment of eczema.18 A preparation made from powdered seeds and roots is frequently consumed orally as part of traditional African practices for treating digestive disorders.19 The native group residing in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan, India, has traditionally consumed a decoction prepared from the plant species for the purpose of alleviating colic inflammation. Additionally, they have employed a mixture of plant ash and oil and used them topically to treat cases of eczema.20 The traditional uses of P. plebeium is mentioned in Table 2.

| Part used | Geographical region | Community of people | Traditional uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole | Orissa | Ethnic people | Treatment of pneumonia | 9 |

| Whole | Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Orissa | Tribal people | In the tribal cultures of Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Orissa, it is utilised as famine food. | 9 |

| Leaf | Utter Pradesh | Rural people | In the rural parts of the Shahjahanpur district of Uttar Pradesh, leaf powder mix with mishri was used to treat menstrual issues. | 10 |

| Whole | Assam | Tribal people | The powdered form is taken orally to treat pneumonia and gastrointestinal issues. | 9 |

| Root | Tamil Nadu | Rural people in Sivagangi | Apply a paste derived from P. plebeium roots twice a day to minimise irritation. | 14 |

| Whole | Pakistani | Pakistan people | To cure ailments like ringworm, inflammation, diarrhoea, liver illness, and pneumonia, aqueous plant extracts are used as a tonic. | 17,21 |

| Whole | Punjab | Local communities | The root decoction, leaf extract, and whole powder paste have several applications both externally and internally, such as serving as liver tonics, treating pneumonia, relieving heartburn, and facilitating regular bowel movements. | 18 |

| Whole | Rajasthan | Tribal people | Plant ash and oil are applied as topical treatments for eczema. A medicinal infusion prepared from a plant species that alleviates colic-related irritation. | 20 |

Phytochemical uses

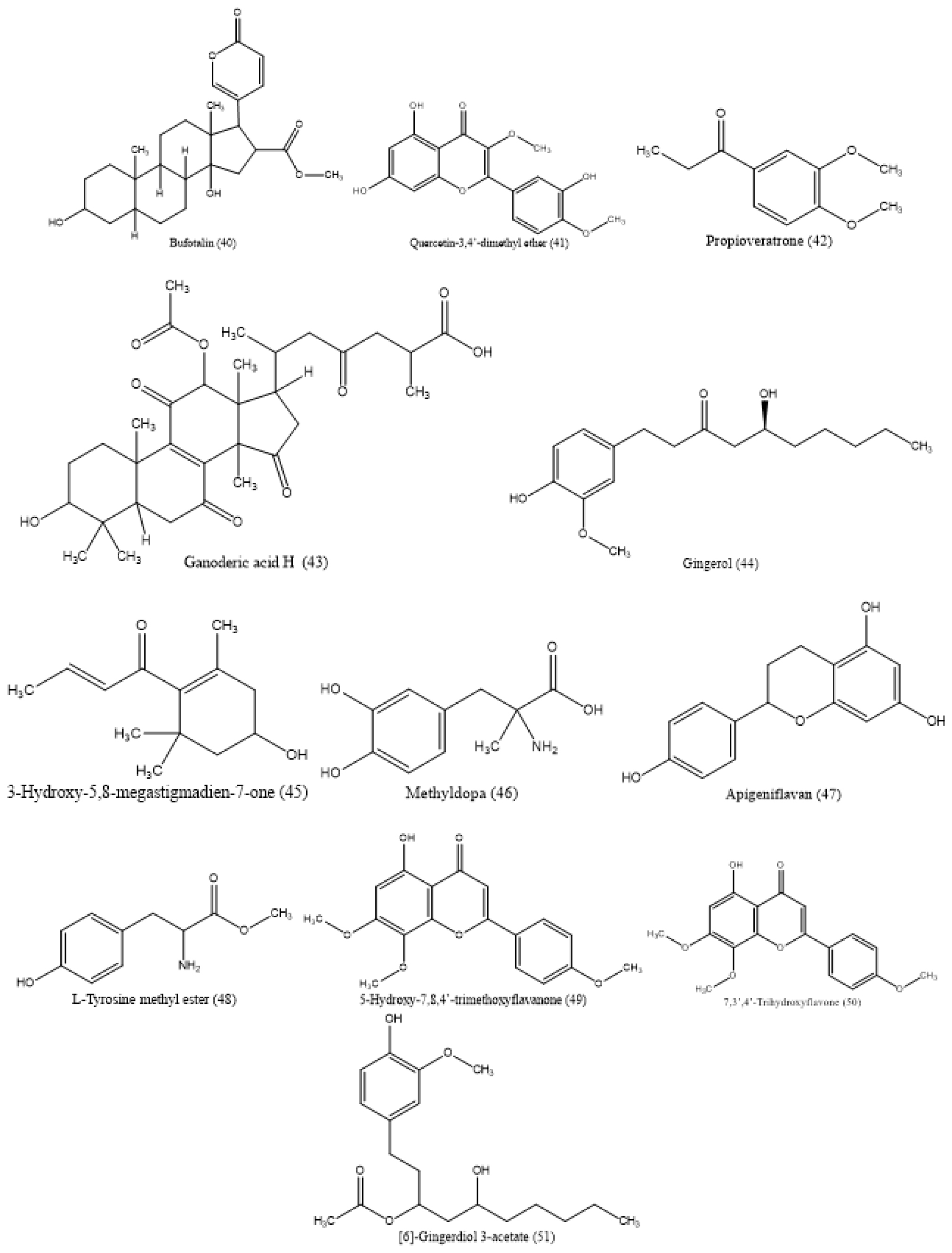

P. plebeium extracts have not been adequately studied for the presence of different classes of phytochemical components. However, a few studies have reported different classes of phytochemical compounds present on P. plebeium plant parts, including its root, flower, leaves, and whole plant. These studies have shown that P. plebeium has a wide range of bioactive phytoconstituents and is considered an important source of bioactive phytoconstituents. The extracts of P. plebeium aerial parts were determined to be phytoconstituents and found to contain essential oils, alkaloids, tannins, and flavonoids.21 The roots of the plant, specifically, contain important compounds such as tannin and oxymethylanthraquinone.19 The leaves of the 15 species were collected in the catchment areas of the river Beas, Punjab. A comparative study of the secondary metabolites was investigated, among which P. plebeium has the highest contents of phenols (31.56 mg/g) and also reports of flavonoids, xanthophylls, and lipids.22 Phenolic compounds possessing antioxidant effects are currently being employed in the processed food sector as a commercial operation. Another studies showed that phenolic compounds are present in almost all parts of a plant and exhibit several health benefits. It has shown antioxidant activity against oxidative stress. It is used as a nutraceuticals and functional foods.23,24 The plant’s flavonoid constituents exhibit a diverse range of activity, covering cytoprotective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antinociceptive, and neuroprotective properties.25 The presence of tannins has also been observed in the leaves of P. plebeium.26 The estimation of secondary metabolite present in the methanol extract of P. plebeium whole plant and its fractions was carried out using the Folin-Ciocalteu method.21 The ethyl acetate fraction of the plant exhibited the highest concentrations of phenolic (89.38 mg/g) and flavonoid (51.21 mg/g) compounds in this study. The reference compounds utilized in this study consisted of gallic acid and quercetin. The Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC/MS) technique was employed to evaluate the isolation phytochemical compound present in the methanolic extract of the whole plant of P. plebeium. This analysis led to the detection and identification of a total of 51 components. Figure 1 displays a full list of chemical compounds, along by their corresponding molecular structures.32

Figure 1:

List of phytochemical compounds identified in methanolic extract of P. plebeium whole plant by UHPLC/MS.

The main flavonoid components of P. plebeium extracts have been shown to be luteolin, isovitexin, and kaempferol derivatives. On the other hand, the principal phenolic components consist of gallic acid and its derivatives, protocatechuic acid, gingerols, and lyoniresinol 9’-sulfate.32 A study was conducted on the flowers of P. plebeium, revealing the presence of seven phytochemical compounds. The phytochemical compounds included in this group are β-Sitosterol, Betulinic acid, Epifriedelanol, Guaijaverin, Oleanolic acid, Quercetin, and Rutin. Figure 2 lists major chemical compounds and their molecular structures.27

Figure 2:

List of phytochemical compounds detected in P. plebeium flower.

Mineral content

The leaves of P. plebeium are a good source of many different kinds of minerals; they are particularly rich in calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, sulphur, and zinc. The study involved a comparative analysis of the mineral content in the leaves of 26 different species. It was observed that P. plebeium exhibited the highest potassium concentration (8.19 mg/100 g) among all the species examined. A significant amount of minerals are contained in leaves, which have traditionally been used by indigenous people and tribes to optimize their health and food security.27 The mineral composition of the whole plant extract was assessed using the proton-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) technique. During the analysis, the plant extract contains the minerals cobalt, copper, iron, manganese, vanadium, and zinc. The analysis also showed that the iron content had the highest concentration (297.62 mg/L), followed by manganese, zinc, copper, and cobalt. On the other hand, vanadium was found to possess the lowest concentration (0.71 mg/L).28 The phytochemical compounds and their pharmacological activities are mentioned in Tables 3 and 4.

| Class of the compound | Name of the compound | Molecular weight | Molecular formula | Pharmacological activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid | 6-Methoxytaxifolin (1) | 334.0689 | C16H14O8 | Anti-inflammatory | 36 |

| 5-Hydroxy-7,2’,3’,4’,5’- entamethoxyflavone(2) | 388.1158 | C20H20O8 | Not reported | ||

| Pongamoside A(24) | 440.1107 | C23H20O9 | Not reported | ||

| Isovitexin(26) | 432.1056 | C21H20O10 | Anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-hyperalgesia, and neuroprotective effects. | 37 | |

| Myricetin 3’-rhamnoside(27) | 464.0955 | C21H20O12 | Anti-mutagenic | ||

| 6-Hydroxyluteolin 6-sulfate(28) | 381.9995 | C15H10O10 | Not reported | ||

| 6-Hydroxyluteolin 5-rhamnoside(29) | 448.1006 | C21H20O11 | Not reported | ||

| Luteolin 4’-sulfate(30) | 366.0046 | C15H10O9 | Antioxidant | 38 | |

| Kaempferol 4’-rhamnoside(32) | 432.1056 | C21H20O10 | Antibacterial | 39 | |

| 3,5,6,7-Tetrahydroxy-4’- methoxyflavone(33) | 316.0583 | C16H12O7 | Not reported | ||

| Ombuin(34) | 330.0740 | C17H14O7 | Anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic. | 40 | |

| Kaempferol(36) | 286.0477 | C15H10O6 | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, cardio-protective, neuroprotective, antidiabetic, anti-osteoporotic, anti-estrogenic, anxiolytic, analgesic and anti allergic. | 41 | |

| Quercetin(37) | 302.0427 | C15H10O7 | Decreasing blood pressure, anti-hyperlipidaemia, anti-hyperglycaemia, anti-oxidant, antiviral, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, neuroprotective, and cardio-protective. | 42 | |

| Rhamnetin(38) | 316.0583 | C16H12O7 | Antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antibacterial. | 43 | |

| Quercetin-3,4’-dimethyl ether(41) | 330.0740 | C17H14O7 | Not reported | ||

| 7,3’,4’-Trihydroxyflavone(50) | 270.0528 | C15H10O5 | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. | 44 | |

| Phenolic | Norvisnagin(6) | 216.0423 | C12H8O4 | Not reported | |

| 6-Galloylglucose(17) | 332.0743 | C13H16O10 | Not reported | ||

| Gallic acid(18) | 170.0215 | C7H6O5 | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer. | 45 | |

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid/Protocatechuic acid(19) | 154.0266 | C7H6O4 | Prevents oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiac hypertrophy. | 46 | |

| 1,2-Digalloyl-β-D- glucopyranose(20) | 484.0853 | C20H20O14 | Not reported | ||

| Lucidin-primeveroside(21) | 564.1479 | C26H28O14 | Not reported | ||

| Lignicol(22) | 240.0667 | C11H12O6 | Not reported | ||

| Lyoniresinol 9’-sulfate(23) | 500.1352 | C22H28O11 | Not reported | ||

| 3,4-Methylenedioxyb enzoic acid(25) | 166.0266 | C8H6O4 | Not reported | ||

| Propioveratrone(42) | 194.0943 | C11H14O3 | Anti-bacterial activity. | 47 | |

| Gingerol(44) | 294.1831 | C17H26O4 | Anti proliferative, anti-tumor, invasive, and anti-inflammatory. | 48 | |

| [6]-Gingerdiol 3-acetate(51) | 338.2093 | C!9H30O5 | Not reported | ||

| Carboxylic acid | 3-Hydroxyadipic acid(10) | 162.0528 | C6H10O5 | Not reported | |

| Erythronic acid(12) | 136.0372 | C4H8O5 | Anti-inflammatory | 49 | |

| 6,7-dihydroxy-4-oxo-2-heptenoic acid(14) | 174.0528 | C7H10O5 | Not reported | ||

| cis-4-octenedioic acid(31) | 172.0736 | C8H12O4 | Not reported | ||

| Chelidonic acid(35) | 184.0008 | C7H4O6 | Analgesic and anti-microbial, intestinal anti-inflammatory. | 50 | |

| Phyto compound | Xanthene-9-carboxylic acid(3) | 226.0630 | C14H10O3 | Neuroprotector, antitumor, antimicrobial | 51 |

| Coriandrone C(4) | 246.0528 | C13H10O5 | Not reported | ||

| 1-Hydroxyp entane-1,2,5-tricarboxylic acid(7) | 220.0583 | C8H12O7 | Not reported | ||

| 5-Acetylamino-6-formylamino-3-methyluracil(8) | 226.0702 | C8H10N4O4 | Not reported | ||

| Paraxanthine(9) | 180.0647 | C7H8N4O2 | Psychostimulant | 52 | |

| 1-Methylxanthine(11) | 166.0491 | C6H6N4O | Anti-cancer | 53 | |

| Quinic acid(13) | 192.0634 | C7H12O6 | Antioxidant, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, anti-microbial, anti-viral, antiaging, neuroprotective, anti-nociceptive and analgesic. | 54 | |

| 2,4,6,3,5-Pentahyd roxycyclohexanone (15) | 178.0477 | C6H10O6 | Antibacterial | 55 | |

| 2-Deoxy-2,3-dehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid(16) | 291.0954 | C11H17NO8 | Anti-diabetic | 56 | |

| (6S)-dehydrovomifoliol(39) | 222.1256 | C13H18O3 | Not reported | ||

| 3-Hydroxy-5,8-megastigmadien-7-one(45) | 208.1463 | C13H20O2 | Not reported | ||

| Phenolic/ Flavan | Catechin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside(5) | 452.1319 | C21H24O11 | Antioxidant | 57 |

| Flavan/Phenolic | Apigeniflavan(47) | 258.0892 | C15H14O4 | Pancreatic cancer, Antioxidant. | 58,59 |

| Flavone | 5-Hydroxy-7,8,4’- trimethoxyflavanone(49) | 330.1103 | C18H18O6 | Not reported | |

| Steroid | Bufotalin(40) | 444.2512 | C26H36O6 | Anti-proliferative and antimetastatic. | 60 |

| Terpenoid | Ganoderic acid H(43) | 572.2985 | C32H44O9 | Anti-cancer | 61 |

| Amino acid | Methyldopa(46) | 211.0845 | C10H13NO4 | Anti-hypertensive | 62 |

| L-Tyrosine methyl ester(48) | 195.0895 | C10H13NO3 | Not reported |

| Class of compound | Name of the compound | Molecular weight | Molecular formula | Pharmacological Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triterpenoid | Epifriedlanol(3) | 428.7 | C30H52O | Not reported | |

| Oleanolic acid(5) | 456.7 | C30H48O3 | Anti-diabetic, anti-viral, anti-HIV, antibacterial, anti-fungal, anti-carcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, gastro protective, hypolipidemic and anti-atherosclerotic, as well as interfering in several stages of the development of different types of cancer. | 63 | |

| Betulinic acid(2) | 456.71 | C30H48O3 | Anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-diabetic, anti-malarial, anti-HIV and anti-tumor. | 64 | |

| Flavonoid | Guaijaverine(4) | 434.3 | C20H18O11 | Anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, antioxidant, anti-diarrheal, anti-microbial, lipid-lowering, and hepatoprotection. | 65 |

| Rutin(7) | 610.521 | C27H30O16 | Anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation, anti-diabetic, anti-adipogenic, neuroprotective and hormone therapy. | 66 | |

| Quercetin(6) | 302.236 | C15H10O7 | Anti-cancer, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cardiovascular, anti-aging, and neuroprotective. | 67 | |

| Phytosterol | β sitosterol(1) | 414.718 | C29H50O | Treatment of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, multiple sclerosis, asthma, and cardiovascular diseases. | 68 |

Pharmacological activity

Antibacterial activity

The bacterial pathogen Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated from a wound infection on the arm of a patient at Cleopatra Hospital in Cairo, Egypt. To assess its susceptibility, the pathogen was subjected to testing using solvent leaf extracts derived from Euphorbia hirta and P. plebeium. The study’s findings revealed that the ethyl acetate extract from both plants exhibited possible antibacterial activity. To effectively combat S. aureus and P. aeruginosa resistance to bacterial infection, the phytochemical components of both plants worked synergistically.29,30

The use of plant extract with Silver Nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) synthesis is of particular interest because it is environmentally friendly and economical. Often, Ag-NPs are widely used in various sectors such as antibacterial research, wound healing processes, drug administration, bio sensing, cancer treatment, and solar radiation detection. The result of this study indicates that P. plebeium-derived Ag-NPs are more stable and have potential antibacterial action. The mechanistic approach of plant extracts with Ag-NPs is mediated by distinct pathways. Firstly, the attachment of Ag-NPs to the bacterial cell wall and membrane is followed by an increase in the rate of penetration and a modification of the signal transduction pathways. Finally, cellular-level toxicity and oxidative stress were reduced by constituents of plant extracts with Ag-NPs.31

Antioxidant activity

The methanol extract of P. plebeium and its various fractions, including hexane, ethyl acetate, and water are the subject of the investigation of its antioxidant activity. The aforementioned fraction had the strongest antioxidant capacity in the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), ABTS (2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), CUPRAC (CUPric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity), and FRAC (Ferrous reducing antioxidant capacity) assays as well. This difference was explained by the different concentrations of phenolics and flavonoids found in ethyl acetate and methanol compared to hexane and water extract. The correlation between the total amount of phenolic and flavonoid content in the extracts and their antioxidant activity is further supported by a Pearson correlation study.32

A study was conducted to determine the antioxidant activity of the aerial parts of P. plebeium using an in vitro technique. The results indicate that methanolic extracts exhibit the greatest level of free radical scavenging activity based on their IC50 value of 43.63 g/mL. The ethyl acetate extract had an IC50 value of 72.62 g/mL, which suggests that it was less effective at scavenging free radicals than the other extracts. The IC50 value of normal ascorbic acid, a commonly used antioxidant, was determined to be 18.34 g/mL. The methanolic and water extracts were found to be the most effective in scavenging nitric oxide. Researchers found that the concentrations of plant extracts increased reduction power, despite their low alkaloid content. Potential antioxidant activity was detected in the ethyl acetate and methanolic extracts. The supporting research for this study suggests that P. plebeium may have potential as a natural antioxidant.21

Anti-diabetic activity

The enzymes α-amylase and α-glucosidase are employed to provide antidiabetic effects in vitro. The highest result for the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was found in water extract (1.78±0.01 mmol/g), however the highest value for the α-amylase inhibitory assay was found in hexane (0.49±0.01 mmol/g). Acarbose used as standard compound for evaluating the effect of antidiabetic activity. P. plebeium can be seen as a possible component to develop novel antidiabetic natural product-based medications.32

Anti-cholinesterase activity

The anticholinesterase-inhibiting activity of the methanolic extract of P. plebeium and its fractions, such as hexane, ethyl acetate, and water, was tested. The findings of the study indicate that the methanolic extract and its fraction exhibit significant inhibitory effects against Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). When compared to the methanol extract (3.63 ± 0. 16 mg/g) and the ethylacetate fraction (3.45 ± 0.56 mg/g), the water fraction (4.03 ± 0.05 mg/g) is more effective against AChE. The hexane fraction has the lowest level of activity (3.35±0.12 mg/g) against Acetylcholinesterase (AChE). While, the hexane fraction had the higher activity against BChE, with a value of 5.62±0.27 mg/g, exceeding both the methanolic extract (1.47±0.06 mg/g) and the water fraction (0.89±0.08 mg/g) in terms of efficacy, the ethyl acetate fraction had no significant activity against Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). The anticholinesterase inhibitory effect of the P. plebeium extract and its fraction towards AChE and BChE may be attributed to the presence of lipids, sterols, phenolics, and flavonoids components. Galantamine serves as a standard compound for evaluating the effects of anticholinesterases.32

Tyrosinase activity

The extract and fractions of P. plebeium exhibited anti-tyrosinase activity. In the study that was performed, several solvents were examined for their respective activities. Methanol (68.34±1.32mg/g), water (65.90±2.69mg/g), and hexane (activity not specified) showed relatively lower levels of activity. Conversely, ethyl acetate displayed the highest level of activity, measuring at 71.89±1.44mg/g. The results of this investigation revealed that the components of the extracts had a synergistic impact. The extract and fractions of P. plebeium contain phytoconstituents suggest that have an impact on the reduction of melanin synthesis in the epidermis layer of the skin. The results of this study indicate that the phytochemicals found in P. plebeium might potentially be used in the formulation of skincare products. Kojic acid is often used as a pharmaceutical agent of reference.32,33

Cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxic properties P. plebeium of the aerial parts were investigated by using in vitro method. Petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water, were used to extract the plant’s aerial parts. The extracts were also tested for their potential cytotoxicity using a Brine Shrimp lethality bioassay. Among the extracts tested in this study, water extract of the aerial part showed the greatest toxicity to Brine Shrimp nauplii, with a LC50 (Lethal concentration 50) value of 23.72 g/mL, while standard drug Vincristine sulphate had a LC50 value 2.47 g/mL. The order at which cytotoxic potential of the test samples decreased was as follows: Water extract>Petroleum ether extract>Methanolic extract>Ethyl acetate extract.21

Anti-inflammatory

A study was conducted to examine the anti-inflammatory properties of the methanolic extract derived from P. plebeium aerial parts. The efficacy of the plant’s anti-inflammatory properties was assessed by in vivo through the method of carrageenan and egg albumin-induced rats paw oedema models. An evaluation of the plant’s ability to suppress protein denaturation was conducted by quantifying the absorbance of the plant extract after treatment with bovine serum and egg albumin solutions. The methanolic extract of P. plebeium exhibited has demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of egg albumin and bovine serum albumin denaturation, with inhibitory rates of 72.9% and 67.5% respectively. In models of paw oedema induced by carrageenan and egg albumin, the plant extract significantly reduced inflammation rate of 48.7% and 40.63%. The results obtained from this investigation could potentially offer evidence of P. plebeium as a therapeutic intervention for inflammatory conditions. The possible anti-inflammatory activities of the P. plebeium methanolic extract may be partially elucidated by the presence of secondary metabolites, along with their precise mechanisms of action.34

Hepatoprotective activity

The hepatoprotective activity of P. plebeium whole plant extracts was examined in a rat model. According to a predetermined regimen, Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4) was administered intra peritoneally to cause liver fibrosis. CCl4 is frequently employed in experimental research to investigate hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. The hepatoprotective efficacy of P. plebeium was assessed through the quantification of Alanine Transaminase (ALT), aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), and gamma-glutamyl trans peptidase (γGT) enzyme levels. The liver tissue was subjected to histological analysis, which confirmed the presence of implanted extracellular matrix and evidence of tissue necrosis. The mRNA expression of genes associated with liver fibrosis was assessed using real-time PCR. The result of the study indicates that the hepatoprotective properties of P. plebeium extracts mitigate liver injury generated by CCl4 in a rat model. The aforementioned investigations collectively indicate that P. plebeium inhibits liver fibrosis due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which effectively interfere with and delay CCl4-induced hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. This study provides evidence to endorse the utilisation of P. plebeium as a therapeutic intervention for individuals suffering from hepatic diseases and concomitant fibrotic conditions.35 The pharmacological activities of P. plebeium shown in the Table 5.

| Activity | Part used | Model | Dose range | Method | Mechanism of action | Standard compound | Extract | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial activity | Leaves | In vitro | 100, 50, 25 mg/mL | Agar diffusion | It inhibits the Staphylococcus aureus. | Ethyl acetate | 29 | |

| Leaves | In vitro | 100, 50, 25, 12.5 and 6.2 mg/mL | Agar diffusion | It inhibits the Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | Ethanol | 30 | ||

| Anti-oxidant activity | Aerial part | In vitro | DPPH Nitric oxide Reducing power capacity. | It is polyphenolic and flavonoid constituents inhibit the scavenging of free radicals and the reduction of nitric oxide label, Cu2+· and Fe3+ ions. | Ascorbic acid, Gallic acid | Petroleum ether, Ethyl acetate, Methanol | 21,32 | |

| Antidiabetic activity | Whole | In vitro | α-amylase and α-glucosidase assay. | The activity of the enzymes α-amylase and α-glucosidase are suppressed by the extract and fraction of P. plebeium. | Acarbose | Methanol | 32 | |

| Anticholinesterase activity | Whole | In vitro | Cholinesterase assays | It has significant inhibitory against AC?E and BChE. | Galantamine | Methanol | 32 | |

| Tyrosinase activity | Whole | In vitro | Tyrosinase assay | The ethyl acetate fractions of P. plebeium exhibited the strongest anti-tyrosinase activity. | Kojic acid | Methanol | 32 | |

| Cytotoxic activity | Aerial part | In vitro | Brine Shrimp lethality bioassay | The cytotoxic activity of P. plebeium may possibly be attributed to its polyphenolic and flavonoid components. | Vincristine sulphate | Petroleum ether, Ethyl acetate, Methanol | 21 | |

| Anti-inflammatory activity | Whole | In vivo | 250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg | Carrageenan and egg albumin | The presence of P. plebeium secondary metabolites maybe related to the inhibition of the synthesis and release of inflammatory mediators. | Ibuprofen | Methanol | 34,35 |

| Hepatoprotective activity | Whole | In vivo | 250 mg/kg | Carbon tetrachloride (CC14) | Anti-fibrotic effects are achieved by reducing α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), tumour growth factor beta (TGF-ß), and collagen mRNA expression. Its alkaloid and flavonoid content have reduced liver inflammation and fibrosis. | Ethanol | 35 |

CONCLUSION

Much scientific literatures focused on phytoconstituents and their pharmacological activity to find alternative treatments for a variety of medical conditions. According to the scientific data presented in the literature, several phytochemical components of P. plebeium have been used for therapeutic purposes in the management of ailments. The scientific literature presents evidence of the pharmacological activity shown by P. plebeium, including its hepatoprotective, antibacterial, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant. A diverse array of chemical components, including flavonoids, phenols, xanthophylls, alkaloids, tannins, and essential oils, were detected in the various plant samples. Additional research is required to determine the precise constituents accountable for those mentioned pharmacological effects. The previously mentioned results possess the potential to provide a basic framework for the execution of chemical, pharmacological, and biochemical research in the future, finally culminating in the discovery and advancement of innovative pharmaceutical substances. In the present context, it is crucial to investigate the phytochemical and pharmacological properties of these plants that have therapeutic relevance.

Cite this article

Nayak S, Kar DM, Choudhury NSK, Dalai MK. An Update on Medicinal Importance of the Plant: Polygonum plebeium R. Br. Int. J. Pharm. Investigation. 2024;14(2):273-88.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are thankful to the Shiksha ‘O’ Anusandhan Deemed to be University for providing continuous support and encouragement in the promotion of scientific works.

The authors are thankful to the Shiksha ‘O’ Anusandhan Deemed to be University for providing continuous support and encouragement in the promotion of scientific works.

ABBREVIATIONS

| P. plebeium | Polygonum plebeium; |

|---|---|

| UHPLC/MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| PIXE | Proton-induced X-ray emission |

| Ag-NPs | Silver nanoparticles |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| CUPRAC | CUPric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity |

| FRAC | Ferrous reducing antioxidant capacity |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| BChE | Butyrylcholinesterase |

| LC50 | Lethal concentration 50 |

| CCl4 | Carbon tetrachloride |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| γGT | Gamma-glutamyl trans peptidase |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Hintsa G, Sibhat GG, Karim A. Evaluation of antimalarial activity of the leaf latex and TLC isolates from Aloe megalacantha Baker in Plasmodium berghei infected mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;14:20 [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Shanley P, Luz L. The impacts of forest degradation on medicinal plant use and implications for health care in eastern Amazonia. BioScience. 2003;53(6):573-84. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Islam MK, Saha S, Mahmud I, Mohamad K, Awang K, Uddin SJ, et al. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by tribal and native people of Madhupur forest area, Bangladesh. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151(2):921-30. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Abbasi AM, Dastagir G, Nazir A, Shah GM, Shah MM, et al. Ethnobotanical and antimicrobial study of some selected medicinal plants used in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) as a potential source to cure infectious diseases. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:122 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Balunas MJ, Kinghorn AD. Drug discovery from medicinal plants. Life Sci. 2005;78(5):431-41. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha PM, Dhillion SS. Medicinal plant diversity and use in the highlands of Dolakha district, Nepal. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86(1):81-96. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Indian biodiversity portal. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Naidu VSGR. India pp. Jabalpur: Hand Book on Weed Identification Directorate of Weed Science Research. 2012:264 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary RK, Oh S, Lee J. An ethnomedicinal inventory of knotweeds of Indian Himalaya. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5(10):2095-103. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Jyotsana S, Painuli RM, Gaur RD. Plants used by the rural communities of district Shahjahanpur, Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2010;9(4):798-803. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Shahidullah M, Al-Mujahidee M, Uddin SN, Hossan MS, Hanif A, Bari S, et al. Medicinal plants of the Santal tribe residing in Rajshahi District, Bangladesh. Am Eur J Sustain Agric. 2009;3:220-6. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Azlim Almey AA, Ahmed Jalal Khan C, Syed Zahir I, Mustapha Suleiman K, Aisyah MR, Kamarul Rahim K, et al. Total phenolic content and primary antioxidant activity of methanolic and ethanolic extracts of aromatic plants’ leaves. International Food Research Journal. 2010;17(4) [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Bunawan H, Talip N, Noor NM. Foliar Anatomy and micromorphology of’ Polygonum minus’ Huds and Their Taxonomic Implications. Aust J Crop Sci. 2011;5(2):123-7. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam S, Rajendran K, Suresh K. Traditional uses of medicinal plants among the rural people in Sivagangai district of Tamil Nadu, Southern India. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(1):S429-34. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Amjad MS, Arshad M, Saboor A, Page S, Chaudhari SK. Ethnobotanical profiling of the medicinal flora of Kotli, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan: empirical reflections on multinomial logit specifications. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2017;10(5):503-14. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Singh Sharma. Polygonum species. In: Secondary metabolites of medicinal plants: ethnopharmacological properties, biological activity and production strategies. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH and Co. KGaA. 2020;3:882-901. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Alamgeer AM, Uttra AM, Ahsan H, Hasan UH, Chaudhary MA. Traditional medicines of plant origin used for the treatment of inflammatory disorders in Pakistan: a review. J Trad Chin Med. 2018;38(4):636-56. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Umair M, Altaf M, Bussmann RW, Abbasi AM. Ethnomedicinal uses of the local flora in Chenab riverine area, Punjab Province Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2019;15(1):7 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Diakses. id= Spigelia+ anthelmia. Tropical Plants Database. Fern K Trop Theferns Info Viewtropical Php?. 2021:13 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Katewa SS, Galav PK. of Traditional herbal medicines from Shekhawati region Rajasthan. Indian J Trad Knowl. 2005;4(3):237-45. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hasan AN, Roy P, Bristy NJ, Paul SK, Wahed TB, Alam MN, et al. Evaluation of In vitro antioxidant and brine shrimp lethality bioassay of different extracts of Polygonum plebeium R.Br. International [journal]. 2015;3(12):97-107. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Vinod K, Anket S, Sukhmeen K, Renu B, Thukral AK. Multivariate statistical analysis of secondary metabolites and total lipid antioxidants. Int J Trop Agric. 2017;35(2):377-81. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Martillanes S, Rocha-Pimienta J, Cabrera-Bañegil M, Martín-Vertedor D, Delgado-Adámez J. Application of phenolic compounds for food preservation: food additive and active packaging. Phenolic Compd-Biol Act. 2017;3(8):39-58. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Choo C, Watawana MI, Jayawardena N, Waisundara VY. An appraisal of eighteen commonly consumed edible plants as functional food based on their antioxidant and starch hydrolase inhibitory activities. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;95(14):2956-64. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Babaei F, Moafizad A, Darvishvand Z, Mirzababaei M, Hosseinzadeh H, Nassiri-Asl M, et al. Review of the effects of vitexin in oxidative stress-related diseases. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8(6):2569-80. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Available fromhttps://cb.imsc.res.in/imppat/phytochemical/Polygonum%20plebe ium

- Gupta S, Srivastava A, Lal EP. Food and nutritional security through wild edible vegetables or weeds in two districts of Jharkhand, India. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(6):1402-9. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Rajan JP, Singh KB, Kumar S, Mishra RK. Trace elements content in the selected medicinal plants traditionally used for curing skin diseases by the natives of Mizoram, India. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7(S1):S410-4. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkhalek ES, El-Hela AA, Hamed El-Kasaby AH, Sidkey NM, Desouky EM, Abdelhaleem HH, et al. Antibacterial activity of Polygonum plebejum and Euphorbia hirta Against Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2018;12(4):2205-16. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antibacterial activity of Polygonum plebeium and Euphorbia hirta against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Merit Res J Med Med Sci. 2020;8(3):25-40. [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee K, Bhagat N, Kumari M, Choudhury AR, Sarkar B, Ghosh BD, et al. Insight study on synthesis and antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles prepared from indigenous plant source of Jharkhand. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2023;21(1):30 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M, Shazmeen N, Nazir M, Riaz N, Zengin G, Ataullah HM, et al. Investigation on the phytochemical composition, antioxidant and enzyme inhibition potential of Polygonum plebeium R. Br: a comprehensive approach to disclose new nutraceutical and functional food ingredients. Chem Biodivers. 2021;18(12):e2100706 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Chen YT, Chiu CC, Liao WT, Liu YC, David Wang HM, et al. Polygonum cuspidatum extracts as bioactive antioxidaion, anti-tyrosinase, immune stimulation and anticancer agents. J Biosci Bioeng. 2015;119(4):464-9. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan HA, Mushtaq MN, Anjum IR, Fiaz MU, Cheema AR, Haider SI, et al. Preliminary research regarding chemical composition and anti-inflammatory effects of Polygonum plebeium R. Br Farm. 2021;69(5) [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Ur Rehman A, Waheed A, Tariq R, Zaman M, Tahir MJ. Anti-fibrotic effects of Polygonum plebeium R. Br. in CCl4-induced hepatic damage and fibrosis in rats. Biomed Res Ther. 2018;5(4):2223-34. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan P, Kalva S, Saleena LM. E-pharmacophore and molecular dynamics study of flavonols and dihydroflavonols as inhibitors against dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2014;17(8):663-73. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- He M, Min JW, Kong WL, He XH, Li JX, Peng BW, et al. A review on the pharmacological effects of vitexin and isovitexin. Fitoterapia. 2016;115:74-85. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed NH, Ammar NM, Al-Okbi SY, El-Kassem LT, Mabry TJ. Antioxidant activity and two new flavonoids from Washingtonia filifera. Nat Prod Res. 2006;20(1):57-61. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Kim MJ. Selective responses of three Ginkgo biloba leaf-derived constituents on human intestinal bacteria. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(7):1840-4. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Deng C, Tan P. Ombuin ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in rats by anti-inflammation and antifibrosis involving Notch 1 and PPAR γ signaling pathways. Drug Dev Res. 2022;83(6):1270-80. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Montaño JM, Burgos-Morón E, Pérez-Guerrero C, López-Lázaro M. A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011;11(4):298-344. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A, Razavi BM, Banach M, Hosseinzadeh H. Quercetin and metabolic syndrome: a review. Phytother Res. 2021;35(10):5352-64. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros DL, Lima ETG, Silva JC, Medeiros MA, Pinheiro EBF. Rhamnetin: a review of its pharmacology and toxicity. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2022;74(6):793-9. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Cao Y, Chen S, Yang X, Bian J, Huang D, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of 6,3’,4’- and 7,3’,4’-Trihydroxyflavone on 2D and 3D RAW264.7 Models. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(1):204 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes FH, Salgado HR. Gallic acid: review of the methods of determination and quantification. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2016;46(3):257-65. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi F, Luceri C, Giovannelli L, Dolara P, Lodovici M. Effect of 4-coumaric and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid on oxidative DNA damage in rat colonic mucosa. Br J Nutr. 2003;89(5):581-7. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Maglangit F, Kyeremeh K, Deng H. Deletion of the accramycin pathway-specific regulatory gene accJ activates the production of unrelated polyketide metabolites. Nat Prod Res. 2023;37(16):2753-8. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- De Lima RMT, Dos Reis AC, de Menezes APM, Santos JVO, Filho JWGO, Ferreira JRO, et al. Protective and therapeutic potential of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extract and [6]-gingerol in cancer: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2018;32(10):1885-907. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Ma T, Xu N, Jin H, Zhao F, Kwok LY, et al. Adjunctive probiotics alleviates asthmatic symptoms via modulating the gut microbiome and serum metabolome. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(2):e0085921 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kim DS, Kim SJ, Kim MC, Jeon YD, Um JY, Hong SH, et al. The therapeutic effect of chelidonic acid on ulcerative colitis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(5):666-71. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn AC, Dobson AJ, Gerkin RE. Xanthene-9-carboxylic acid. Acta Crystallogr C. 1996;52(6):1486-8. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Orrú M, Guitart X, Karcz-Kubicha M, Solinas M, Justinova Z, Barodia SK, et al. Psychostimulant pharmacological profile of paraxanthine, the main metabolite of caffeine in humans. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:476-84. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Youn H, Hee Kook Y, Oh ET, Jeong SY, Kim C, Kyung Choi E, et al. 1-methylxanthine enhances the radiosensitivity of tumor cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85(2):167-74. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Benali T, Bakrim S, Ghchime R, Benkhaira N, El Omari N, Balahbib A, et al. Pharmacological insights into the multifaceted biological properties of quinic acid. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. ;2022:1-30. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Daum SJ, Rosi D, Goss WA. Mutational biosynthesis by idiotrophs of Micromonospora purpurea. II. Conversion of non-amino containing cyclitols to aminoglycoside antibiotics. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1977;30(1):98-105. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Minami A, Fujita Y, Shimba S, Shiratori M, Kaneko YK, Sawatani T, et al. The sialidase inhibitor 2,3-dehydro-2-deoxy-N-acetylneuraminic acid is a glucose-dependent potentiator of insulin secretion. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5198 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Kim JS, Kang KA, Kim JM, Won Hyun J. Cytoprotective effects of catechin 7-O-β-D glucopyranoside against mitochondrial dysfunction damaged by streptozotocin in RINm5F cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2010;28(8):651-60. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Das R, Agrawal S, Kumar P, Singh AK, Shukla PK, Bhattacharya I, et al. Network pharmacology of apigeniflavan: a novel bioactive compound ofTrema orientalis Linn. in the treatment of pancreatic cancer through bioinformatics approaches. 3 Biotech. 2023;13(5):160 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Costa G, González-Manzano S, González-Paramás A, Figueiredo IV, Santos-Buelga C, Batista MT, et al. Flavan hetero-dimers in the Cymbopogon citratus infusion tannin fraction and their contribution to the antioxidant activity. Food Funct. 2015;6(3):932-7. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Jung HJ. Bufotalin suppresses proliferation and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting the STAT3/EMT axis. Molecules. 2023;28(19):6783 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Grieb B, Thyagarajan A, Sliva D. Ganoderic acids suppress growth and invasive behavior of breast cancer cells by modulating AP-1 and NF-kappaB signaling. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21(5):577-84. [PubMed] | [Google Scholar]

- Yassa R. Lithium-methyldopa interaction. CMAJ. 1986;134(2):141-2. [PubMed] | [Google Scholar]

- Castellano JM, Ramos-Romero S, Perona JS. Oleanolic acid: extraction, characterization and biological activity. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):623 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Li H, Zhang S, Lu H, Chen Q. A review on preparation of betulinic acid and its biological activities. Molecules. 2021;26(18):5583 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Tomar M, Amarowicz R, Saurabh V, Nair MS, Maheshwari C, et al. Guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves: nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and health-promoting bioactivities. Foods. 2021;10(4):752 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Chua LS. A review on plant-based rutin extraction methods and its pharmacological activities. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150(3):805-17. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Ye H, Kamaraj R, Zhang T, Zhang J, Pavek P, et al. A review on pharmacological activities and synergistic effect of quercetin with small molecule agents. Phytomedicine. 2021;92:153736 [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]

- Marahatha R, Gyawali K, Sharma K, Gyawali N, Tandan P, Adhikari A, et al. Pharmacologic activities of phytosteroids in inflammatory diseases: mechanism of action and therapeutic potentials. Phytother Res. 2021;35(9):5103-24. [PubMed] | [CrossRef] | [Google Scholar]